I’ve been thinking about compassion lately. It’s impossible not to, with everything that’s going on in our world. Terrorist attacks, increased racial tensions, insensitivity toward other minority groups, and the most vitriolic U.S. presidential election I can remember (notice the timing of this post, fellow Americans?)… From a social perspective, 2016 has been a bleak year, and I’m deeply worried about where we as a society are heading.

But let’s not discuss politics. Instead, let’s focus on a topic that I think many of us will agree on: the power of compassion in literature. By compassion, I mean moments when characters show kindness, mercy, and similar qualities. These actions can draw us closer to those characters, move us to tears, and make those stories all the more memorable. And during these turbulent times in our world, finding – and writing – stories that demonstrate compassion may be more important than ever.

There’s Some Good In This World, and It’s Worth Writing About

It’s easy to get caught up in the whirlwind of negativity. Turn on the TV, or scroll through your social media feed – BAM! It’s there. Some nights I “disconnect” from all of that on purpose, and not out of apathy. Instead, the empath in me is drained. I absorb the toxicity like a sponge, and then it lingers until I find a way to “squeeze” it out of my system. And when you’re a writer, sometimes the safest place for that overwhelm to go is on the page.

Like Vaughn Roycraft says in this piece at Writer Unboxed, empathy is an unspoken job requirement for writers. We need it so we can understand the world at large and portray it realistically – and, in a way, attempt to make sense of it – in our stories. That absorption takes its toll on us after a while. But because of the nature of work, it doesn’t ever go away. It’s almost as though we need to remember to look for the good in the world, to make that extra effort to find people, events, or ideas that give us hope.

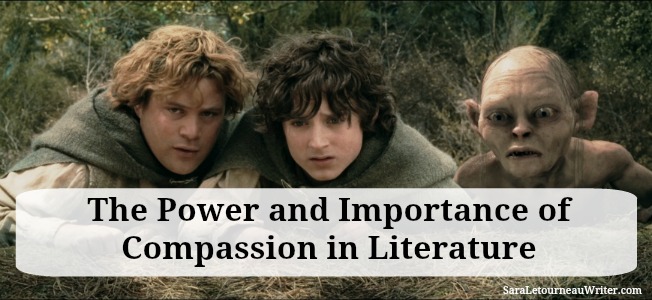

Can we find those beacons in real life? Absolutely. But why not look for them in the stories we read and/or write, too? As Samwise Gamgee says in the Two Towers film:

Sure, it sounds idyllic, but it also bears a goldmine of truth. Stories have this stunning power to make one’s tiny corner of the world a better place, even for just a few hours. They make us laugh, cry, and ride a rollercoaster of emotions. They open our eyes and shift our lives in ways we never thought possible. And when I think about the literary moments that moved me most, many of them are acts of compassion. This post from last February shares a handful of those scenes; and if given the time, I could expand that list several times over.

Compassion Still Has a Place in Literature and Humanity

But what is it about compassion that makes it such an endearing quality? Maybe it’s because characters (and real people) sometimes offer it under less-than-ideal circumstances, or to others who might not deserve it. We can debate whether Frodo should have let Gollum guide him and Sam into Mordor, but no one can deny that Frodo did what he thought was right by showing Gollum mercy. Thus, he was more humane toward a slippery character than many of us probably would have been.

That’s the point behind an act of compassion in real life and in fiction: It demonstrates the best of humanity. It gives us faith that good people still exist when others choose less wisely. It reminds us to show genuine kindness to others, selflessly and fearlessly. As the Dalai Lama once said, “Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries. Without them, humanity cannot survive.” That phrase rings achingly true for me right now.

The plot of A.J. Hartley’s “Steeplejack”show members of a South African-esque city’s three races collaborating to solve a murder mystery.

Maybe my sensitivity to the recent dearth of compassion explains why I’ve been devouring books like chocolate chip cookies. (Figuratively speaking, of course.) Many of my reading choices this fall have been AMAZING, and not just for their world-building, writing, or other elements. Rae Carson’s Like a River Glorious, Ruta Sepetys’s Salt to the Sea, A.J. Hartley’s Steeplejack, Yann Martel’s Life of Pi – they lifted my spirits because their characters took the time to show kindness, tolerance, or sympathy toward others. Thus, these and other books offered more than escapism. They offered an antidote to the hostility I’ve witnessed so much of lately.

This also routes back to the #WeNeedDiverseBooks campaign. Readers, writers, and publishing experts are advocating for more diverse characters in YA and speculative fiction not only for the sake of representation and inclusion, but also because it helps foster a more tolerant and compassionate readership. I’ve enjoyed reading about characters who are different from me ever since I was young. Those early diverse reads allowed me to see the world and its challenges in new ways, and taught me to be accepting of others. And now, as I pursue a writing career, I want to ensure my stories open similar windows to readers – not in a preachy manner, but in a natural and conscientious way.

Danaerys Targaryen (Emilia Clarke) is embraced by the slaves she liberated on “Game of Thrones.”

Balancing Compassion with the Ugliness of Reality

I’m not suggesting, though, that stories need to be all sunshine and rainbows. If the world a character lives in has no conflicts, unsavory people, or other problems, it wouldn’t be believable. Therefore, the challenge that writers face in this regard is balancing compassion with realism, including the ills of the story’s world.

Take George R.R. Martin’s Song of Fire and Ice series (and the TV show Game of Thrones), for example. In this intensely and violently realistic world, characters unflinchingly commit one atrocity after another: political corruption, incest, infidelity, slavery – and the list doesn’t end there. Some of these acts are considered acceptable in certain cultures, too. The audience might be appalled by the frequent grimness, but these issues are consistent with Martin’s vision for the series and are currently (or used to be) issues we’re dealing with in our own world.

Not every character in Martin’s world lacks compassion, though. Danaerys Targaryen, after being victimized by her brother Viserys and his benefactors, sympathizes with oppressed peoples and has made ending slavery one of her priorities in her campaign across Essos. Jon Snow also stands up for other characters, protecting Samwell Tarly from bullies at the Night’s Watch and establishing a tenuous yet respectful relationship with the Free Folk. These and other instances of compassion in Martin’s stories aren’t meant to make us forget the more controversial moments. Rather, they’re a continuation of the world’s reality, offering the good that can be found amidst its grit.

Plenty other stories in both genre and literary fiction juxtapose compassion and cruelty in various ways. That contrast is something we need to consider when working on our own stories. In my WIP’s world you’ll find injustices such as oppression, poverty, and prejudice. You’ll also find advocacy against those injustices, as well as friendship, loyal alliances, and cooperation. The characters contribute to this contrast, too. Some are flawed but have good intentions, while others are morally ambiguous. Because of all this, my hope is that readers will find this world believable for the good, grey, and ugly that exists, and that the good will give them hope for a brighter future – in the story’s world, and in ours.

Tyrion (Peter Dinklage) and Jaime Lannister (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau) have a brotherly conversation on “Game of Thrones.”

Even Anti-Heroes Are Kind Sometimes

What happens, though, when a character falls into that grey area? If he has no qualms about crossing certain moral lines, does that make him deplorable? Some readers might think so. But what if this character willingly says “no” to other reprehensible acts, or refuse to betray the morals he does believe in? Here we can make a case that an “anti-hero” is capable of compassion. He may not think of himself as a “good guy” per se, but he hasn’t completely lost touch with his humanity.

One of my favorite literary anti-heroes of late is Jaime Lanniser (Song of Ice and Fire / Game of Thrones). A brash and arrogant knight, he’s reviled throughout Westeros for having killed King Aerys Targaryen, and perhaps by readers for his sexual relationship with twin sister Cersei. But not everything Jaime does is dishonorable. He loves his younger brother Tyrion despite his physical malformations, and defends Tyrion when Cersei insults him. He also rescues Brienne of Tarth from Harrenhal and Tyrion from the Red Keep’s dungeons during A Storm of Swords because he cares about both characters. So, for a man who often acts out of pride or selfishness, Jaime is also capable of compassion.

An illustration of Kaz Brekker from Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows Duology.

Kaz Brekker from Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows Duology (Six of Crows, Crooked Kingdom) is another recent anti-hero. As a lieutenant of the Ketterdam gang The Dregs, Kaz has robbed, lied, broken bones, and killed to secure the Dregs’s interests and further his own ambitions. Most of his interactions show what you might expect from him: a callous, calculating, highly confident young man who demands loyalty and competency from others but little else. Even with his sympathetic backstory, some critics of the series have found it difficult to like Kaz because of his willingness to do whatever it takes to get what he wants and make his plans succeed.

Well, not entirely “whatever it takes.” It’s clear in both books that Kaz has never forced himself on women and doesn’t engage in human or sex trafficking. In fact, one of his most humane moments comes from his and Inej Ghafa’s backstory, when Kaz paid off Inej’s contract at a brothel so she could work for him as a spy. He may have brought her from one dangerous profession to another, but what Kaz did was, in his unique way, an act of kindness. He changed Inej’s life for the better by giving her employment where she could be respected for her abilities and not abused for pleasure’s sake.

What’s most important about an anti-hero is that he isn’t just a “bad boy” (or “bad girl,” in an anti-heroine’s case). Like real people and not-so-grey characters, he’ll stand up for his goals, desires, and beliefs, but not for anything that contradicts them. And when he reaches that point, he might choose the option that readers would agree is the better one. His acts of compassion will be few and far between, and more difficult to spot because of who he is. But they’ll be among the acts he’ll be most remembered for, and they might redeem him in the readers’ eyes.

It’s Our Turn to Wield the Power of a Storyteller

This brings us back to the power of storytelling during times like now. When we sit down with a book, we might be upset or frustrated by things in our personal life or the turbulence of the world at large. But then we read the next chapters for characters like Frodo, Dany, or Jon (or heck, even Jaime and Kaz at their best), and we think, “Wow. I didn’t know how much I needed that character and his/her story until now.”

Stories don’t necessarily disengage us from reality. Instead, they encourage us to think about our world and its many shades on our own time, and in our own way. Through the characters’ experiences, we see humanity at its best and worst, then pause to consider, evaluate, and decide for ourselves. But most importantly, the good that we see in stories reminds us that we can still hope, that people can still be kind toward one another, that we can be forgiven for our mistakes.

And what about the stories we write? The moment you give a piece of writing to someone – a printed book, a draft for beta-reading, a poem or blog post online – it becomes theirs to experience. They become your reader. You now wield that power that you’ve witnessed from the authors you have read. It’s a power that comes with great responsibility, but also with profound impact when used carefully and correctly.

One of the points I’d made in a #1000Speak post last April was that writing demands us to explore every angle of humanity, from its darkness and pain, to its light and beauty. We should exercise empathy and intelligence as we craft our stories, and remember that no one and no place is 100% good or bad. But we can’t completely omit the good, either. Fiction of all genres, including speculative fiction, should reflect reality in some manner. Why not show examples from throughout reality’s spectrum, including the good?

That last sentence reminds of a discovery I recently made. As I wrote earlier as well as in this DIY MFA article over the summer, the current social and political climate has me frightened and worried. But when I work on my WIP, I can’t help but think, “I’m so grateful for this story. right now” Because (not to spoil things, but it’s crucial for this topic) the young woman at the center of this story learns about the power of compassion in a world that’s sometimes lacking it, and that lesson changes her in a positive way. I’m also in the process of gathering a diverse beta-readership for my WIP so I can gain a broader range of perspectives and a better understanding of how people might view the book’s contents.

It’s strange, because the WIP is in no way a product of or reaction to current issues. (As of today, I’ve been working on it for almost 4 years.) But its timing with external events isn’t something I can ignore. I don’t know how well (or poorly) I’ve done my job as the writer yet, but my beta-readers will let me know in time. And in my heart of hearts, I hope it allows them to feel how I’ve felt about some of the books I’ve recently, and made their world a better place for a little while.

How important do you think compassion is in real life and in literature right now? What acts of compassion in stories you’ve read have stuck with you? If you’re a writer, how does your WIP balance the grimness or grey areas of reality with acts of kindness?

Another superb, thought-provoking article, Sara:). You’re right – compassion is important and is not discussed frequently enough by writers or readers and yet it is the glue that keeps humanity from slaughtering each other? It’s easy to be loving and kind to those of our own clan and kin – but what about sympathy and help for Others, those alien to us? Who look, act, speak and smell differently to us? Our monkey gene default is to immediately treat those folk with suspicion and fear – surely if we’re to lay any kind of claim to be progressing as a species, it must be how we react to those less fortunate to ourselves who are not our clan, our kin… This is something that Jo Walton very much addresses in her trilogy Thessaly, which explores the concepts propounded by Plato in ‘The Republic’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Sarah. 🙂 I started typing a longer comment, but realized I was only repeating things I’d said in my post. So… I’m just glad to know that other people feel the same way as I do about this subject, and agree that it should be discussed more often (or at least as often as us finding solutions to the problems we’re currently facing – but that’s another subject entirely).

I haven’t read Jo Walton’s Thessaly trilogy (or any of her work yet, shame on me), so I’ll have to look into that. But you’ve also read UKLG’s The Left Hand of Darkness, right? How Genly Ai learns to accept the Gethenian’s culture and androgyny and befriends Estraven – he wouldn’t have been able to complete his mission without Estraven, and without growing into a more understanding character. That’s a good example of not only compassion in literature, but how compassion helped characters reach their goal and find common ground despite their differences.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, you’re right! And Terry Pratchett is also an author who regularly used to espouse compassion and acceptance in his Discworld novels. It was always the characters who were able to encompass the difference in others who prospered.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I feel it goes without saying for me that compassion is very important in real life, and therefore also in what we may read or write or watch. Compassion reminds us to stop thinking about “me” and start thinking about “others,” and consider how another person’s day has been, and if they need some encouragement or a helping hand.

Compassion is an important theme for me in the stories I write, and for this very reason. I want to help spread kindness, love and compassion, and hopefully make someone’s day a little bit better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

^^ I love all of this, Elizabeth. Especially this morning. I’ve always done my best to be kind and accepting toward people, and I’m going to do everything I can – especially in my writing – to do just that with even more intention and belief now.

Thanks for commenting. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤ I'm glad to hear it, Sara. This world needs more kindness and compassion, so let's do the best we can. *hugs*

LikeLiked by 1 person

Compassion means a lot to me in stories. It annoys me the most when characters seemingly have no compassion at all. I usually dislike a character who has no compassion. Great post, Sara!

storitorigrace.blogspot.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

^^ Same here. If a character lacks compassion, it’s as though they’ve lost their humanity (and to a degree, their believability as a fictional character). It’s something to keep in mind as we write our own characters.

Thanks for your comment, Tori. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Compassion is very important. I read crime novels mostly and the crimes are always atrocious but the killer always has ‘feelings’ and misguided thoughts, of love even, and I don’t hate them as much as I should. The few books I’ve read where the feelings are completely missing (about manipulators and sociopaths) like Blood Related and He Counts Their Tears, I didn’t like these books so much. I can’t identify or imagine how it is to be without any compassion so yes I crave it in a book. Great thought-provoking post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s an interesting point, Inge. Antagonists, including murderers and other perpetrators in crime stories, are human beings just like protagonists and any other character. Which means they should have fears and vulnerabilities. They should feel love, sympathy, and kindness toward some people, things, and ideas. It’s a lot like with the anti-heroes… And when they don’t have those vulnerabilities, they’re much more difficult (and in some cases, impossible) to relate to. They’ve lost their humanity, in a sense. I can think of a number of characters I’ve read in speculative fiction who are like that, too. And they’re difficulty to identify with, as well. So I know what you’re talking about, from a writer’s perspective and a SF&F reader’s perspective.

Thanks for stopping by and commenting, Inge. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Writing Links in the 3s and 5…11/14/16 – Where Genres Collide

Sara, this was such a poignant post! I always find that I leave a story with more satisfaction if within it there was some display of compassion or the like. I always find it most difficult to nail the compassion with my antagonists, mostly because I haven’t given them enough room to grow in the past. It’s something I’m working on.

Nothing really impresses me more than a genre read with real humanity at its heart. I’ve found a surprising amount in Dean Koontz’s Odd Thomas series, a dark urban fantasy of sorts.

Thank you for a thought-provoking post that resonates both in the realm of literature and in our reality these days ❤️

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Life in Rhymes / Vida em Versos and commented:

There’s a line in one of my poems that goes: “Dearth of compassion inflicting the Earth…” In moments of crisis, it’s hard to find humanity, but it’s there… it’ll always be… hidden or lost as it may seem at times.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Mystery Blogger Award | Sara Letourneau's Official Website & Blog

This is so beautifully put! I love the idea that we can use stories and words to inspire others to compassion! I think many of the most memorable parts of stories are precisely those where kindness and mercy and compassion are shown. I’d like to believe that readers can take some of that with them when they’re done reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope so, too. And I think that was one of my main motivations for writing this post about 2 years ago, and why it’s still relevant today. Sometimes it feels like the world is burning down (figuratively speaking, but it might as well be literal), and there’s so much fear, anger, and division. So when I read a book that shows compassion, tolerance, and other forms of empathy at its heart – or if I hear of somebody doing a real-life act of generosity or kindness – it makes me feel as though we still have a chance. ❤

LikeLike

This is such a beautifully written post! You being up so many wonderful points, love! Compassion is such a key element to include in novels, and I especially love the bit you spoke about regarding anti-heroes and their ability to be kind. Most of the time, these characters are not so black-and-White, and it’s fasivnating seeing how despite whatever vicious acts they might engage in, they still possess a sliver of humanity. ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Kelly! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. Writer’s write a lot about compassion, but they actually ‘have’ compassion? The writers I know, are some of the meanest people I’ve ever met. There’s always expectations, though. Beautiful piece. 💞

LikeLike